...Turner's contemporary detractors quite simply possessed no adequate framework within which to understand his achievement. In the early part of the nineteenth century landscape painting was still judged in terms of seventeenth-century Italian idealist and Dutch naturalistic models. By these standards, even Turner's more conventional paintings look poorly executed and disorderly. Lacking a structured idea-space within which to make sense of what Turner was trying to do, the critics simply decided he was mad.

J. M. W. Turner - Dido Building Carthage (1815)

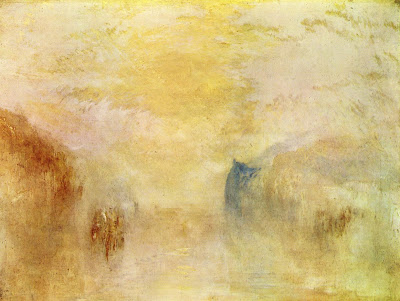

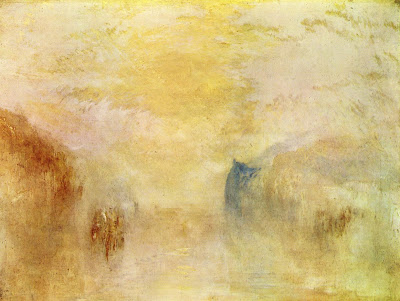

A glance at just two paintings suffices to show how far Turner traveled and how revolutionary a painter he became, especially in his later years. The first, Dido Building Carthage, consciously imitates seventeenth-century landscape painting that Turner modeled himself on in his early period. The second, Sunrise, with a Boat Between Headlands, is a work, entirely characteristic of his late period, "which could be shown with the canvases of any Abstract Expressionist."

No painter except Picasso advanced so far from the painting styles he inherited, or bequeathed to those who came after him such a radically new vision of what painting could be. Turner's influence largely skipped over the art of the next five or six decades, but the revolution he wrought anticipated some of the most profound characteristics of twentieth-century painting.

J. M. W. Turner - Sunrise, with a Boat Between Headlands (1845)

His late paintings, of which Sunrise is a characteristic example, constitute an art in which light and color predominate over form, kinetic force replaces classical stasis, abstraction undermines faith in the reliability of visual representation, and (in seeming anticipation of relativity theory) space and time merge. To put it simply, Turner is the first truly modern painter.10

Great painters do more than produce beautiful or inspiring images. They succeed in transforming the context of painting itself, the space in which it can unfold in the future. This act of artistic paradigm creation is the work of the imaginative intelligence par excellence, transporting the mind to as yet unexplored regions where reason cannot go.

Turner possessed an imaginative intelligence of the highest order. His most radical achievements—liberating color, reducing figural representation to the point of pure abstraction, and making the process of painting meaningful in its own right—were, in modern business parlance, game-changing moves, representing a huge creative leap whose influence we can still recognize in the art of our own time. But the impulses that led him along this path flowed less from his own abundant artistic talent than from his passionate engagement with and integration of two of the most powerful emergent idea-spaces of the nineteenth century: Romantic art and empirical science. The very antithetical tension between them seems to have set his imagination on fire.

Turner's development as an artist affords a window into how the imagination does some of its most radical and exciting work: creating a new idea-space by integrating intelligence embedded in widely separated existing or emergent spaces. The unfolding of Turner's thinking as an artist shows how he allowed key ideas from Romanticism and science to play off one another until they finally—and powerfully—fused.

- Richard Ogle