In the first decade of the twentieth century, art and science both underwent profound revolutions. In 1905, Albert Einstein published his paper on the special theory of relativity that forever changed our conceptions of space and time. In 1907, Picasso painted the picture that irrevocably set painting on a different course. Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, with its fractured planes, was the immediate precursor to cubism, the movement that in many ways constituted the powerhouse for twentieth-century art. As we'll see, the two events were hardly disconnected. In looking at cubism, our main focus will be not on the rise of the movement itself, but rather the way in which it constituted an idea-space in which the law of spontaneous generation began to play a key role in enabling the viewer of cubist paintings to discover meaning in them.

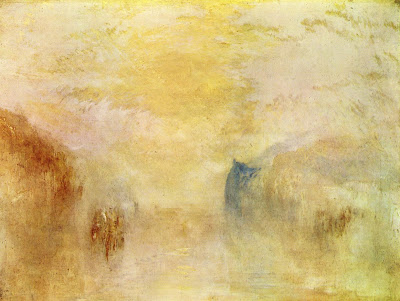

Cubism's status as a revolutionary art movement is hardly in doubt. As the art critic Robert Rosenblum notes, cubism "altered the structure of Western painting to a degree unparalleled since the Renaissance," achieving this goal by means of its "drastic . . . shattering and reconstruction of traditional representations of light and shadow, mass and void, flatness and depth." To grasp how radical a break with the past cubism represents, consider for a moment a typical impressionist painting such as Renoir's Le Moulin de la Galette (painted in 1876—but almost any post-Raphael /pre-Cezanne painting would do). The scene shows several figures seated at a table outside a café, while dancers swirl in the town square behind them. Although impressionism of course effected its own important innovations, particularly in regard to the treatment of color perception, it otherwise generally conforms to the classical canons of figurative art. The rules of perspective and foreshortening are obeyed, with more distant figures drawn significantly smaller than those in the foreground and receding along lines radiating from a single focal point. Similarly, light and shadow are treated in a natural and realistic fashion, and the conventional relationship between form and space (i.e., that forms fit the spaces they would occupy in real life) is rigorously observed.

Now let's look at a typical cubist painting, Picasso's Landscape with Poster (1912). Immediately we recognize we are in a completely different kind of pictorial space. Classical perspective has been banished, along with the rest of the grammar of figurative painting. The unity of the picture space has been fragmented into multiple planes representing varying points of view simultaneously, as though what is being captured is the result of someone walking about. The static snapshot viewpoint of Renoir has thus given way to a dynamic configuration—suggestive of movement—in which, as in relativity theory, space and time have merged. Conflicting light sources, suggesting multiple perspectives, are presented within a color scheme that verges on the monochromatic. Figuration, although not abandoned altogether, has been severely subordinated to the abstract geometry of rectangles, trapezoids, and semicircles. The painting, far from attempting to create an illusion of an actual scene, constantly moves in and out of being an autonomous object in its own right, creating its own level of reality and obeying its own internal aesthetic logic. A crucial dimension of this logic, which is representative of the intelligence embedded in the idea-space of cubism as a whole, is the way in which the painting is structured so as to enable the viewer to spontaneously generate patterns of meaning. The viewer shifts from being a passive spectator to an active participant in constructing the painting's interpretation.

Looking at the painting more closely, for example, we notice, in addition to various schematically depicted objects (exteriors walls, doorways, windows), several words displayed quite prominently: Pernod across the top of a bottle, Leon inscribed on a billboard in bold cursive script, and near the bottom of the painting, Kub 10c. Words in fact appear repeatedly in cubist paintings—brand names, numerals, shop signs, and various parts of newspapers. As in the case of other forms of figuration, words and letters move in and out of representing something and becoming aesthetic objects in their own right, integrated into the remaining abstract forms.

This use of letters in cubist iconography, as Rosenblum points out, bears directly on the central issues of how painting relates to the real world and the role of the viewer in shaping how the artwork is experienced.28 In the case of Renoir's painting, life is depicted with sufficient realism to give the illusion of actuality, leaving the viewer with little to do except passively gaze at it. In Picasso's painting, on the other hand, objects are not so much depicted as denoted by means of a visual sign. A flat rectangle with writing on it stands for a billboard, a line in the shape of an inverted J for an archway. Cubist forms thus point to objects in roughly the same way that words do—not by means of realistic figural representation but via visual signs. We are left to read their meanings into them, aided by motifs such as bottles, glasses, archways, and musical instruments that are used over and over. The viewer, in other words, actively shapes the meanings of the painting.

What are we to make of all this? From one perspective, cubism looks like an enormous impoverishment of the rich language of classical figurative painting. "What a loss to French art!" a Russian collector remarked on seeing Les Demoiselles d'Avignon. Yet in breaking decisively with the five-hundredyear-old tradition of depicting the illusion of real life, cubism inaugurated a new era. As one critic put it, "This is the moment of liberation from which the whole future of the plastic arts in the Western World was to radiate in all its diversity."

Cubism shifted from realistic representation to the spontaneous generation of implicit meanings for viewers themselves to discover, play with, and even elaborate. Far from being an impoverishment of art's expressive powers, cubism in fact opened up a vast new array of possibilities. In the process, it changed forever the idea-space in which art evolves. Its new grammar of abstraction, flattening, fragmentation, analytical decomposition of objects, simultaneous perspectives, and multiple ambiguities made possible an immense enrichment of meaning along manifold dimensions, as well as a deepening and broadening of art's metaphysical content.

The constant interplay between elements on different levels, allowing simultaneous meanings (visual and verbal puns) to coexist and multiply, enriched art with irony, humor, and ambivalence. By the same token, it radically undermined any simple reliance on a literal, unitary interpretation of perception. Time and space became integrated in a single flattened plane. Paintings seemed to flip back and forth between semiabstract objects creating their own reality and semifigurational works pulling the viewer back into the real world. Indeed, a typical cubist painting seemed quite profligate in the levels of reality it engendered: almost completely abstract, geometric denotation (a cube for a building), semiaccurate figuration (bottles, buildings, doorways), accurately drawn symbols (letters/words), and finally the intrusion of real objects (collage).

Cubism's witty permutations of these levels and elements and its deliberate use of commonplace objects may seem playful, but it effectively initiated a complete metaphysical reframing of art from the ground up, raising questions destined to shape the progress of art for decades to come: How does a work of art relate to the real world? How is perceptual space organized? What is the role of the viewer—passive spectator or engaged participant, continuously constructing and reconstructing an artwork's meaning? What are a painting's borders, where does art stop and the real world begin, what is inside versus outside the frame?

The depth, range, and power of the revolutionary cubist aesthetics and metaphysics, embodied visually in the radically new space it created for the artistic imagination to unfold in, lies in its discovery of a universal truth about the fundamental calculus of creativity. In effect, cubist art exploits a version of the law of spontaneous generation. Identifiable elements in a painting form a network of related elements (visual resonances and analogies, verbal puns, etc.) that invite the viewer to construct out of them a series of meaningful patterns. Furthermore, as each pattern emerges, it subtly shifts the relationships among the remaining patterns, giving rise to still larger patterns (consider how the recognition of a sexual pun in the middle of a painting might change the interpretation of other elements). Thus in a cubist painting, what shapes the viewer's aesthetic experience is the ongoing generation of meaning that is spontaneous, emergent, and self-transforming. By cocreating with the viewer multiple layers of meaning, this new grammar of painting enabled art to express more authentically the multidimensionality and complexity of human experience.

Cubism vastly enriched the idea-space of twentieth-century art—for artists and viewers alike. In the process it launched a highly energized wave of change that continued to sweep through art over the next seventy years, from constructivism and the Dutch De Stijl movement to conceptualism and pop art.

As any art history textbook will tell you, cubism was invented by Braque and Picasso. The workings of genius in this achievement are not to be denied. But let's ask Kauffman's intriguing question: Whence this order? Did it spring fully formed from the heads of Braque and Picasso? Are they alone responsible for one of the greatest revolutions in the history of art? Or were there, in Kauffman's phrase, "vast veins of spontaneous order" lying at hand that Braque and Picasso discovered and mined? In short, was the new order cubism represented in reality an example of coevolutionary change, the spontaneous and emergent result of two painters of genius interacting with the laws of self-organization?

The foregoing analysis of cubism suggests precisely that. The break cubism made with the past was above all a break with realistic representation in favor of abstraction. Not the purely nonrepresentational abstraction of Kandinsky, but a much more analytic, formal, geometric abstraction. That this occurred at the very same time that Einstein was overthrowing Newton by reintroducing geometry into physics, while simultaneously undermining our commonsense faith in the reality depicted by falling apples, is no mere coincidence, as Arthur I. Miller has brilliantly demonstrated in his recent book, "Einstein, Picasso."

It was part of Picasso's genius to have intuitively recognized very early the significance of this historic scientific shift. Furthermore, once the basic move to abstraction had been made, much else followed almost automatically. Abstract form, like mathematics itself, proved to be a rich generative engine. There are always more sets of things than things. Picasso and Braque, influenced by radical new theories in mathematics and physics that destroyed the unity of a single perspective, discovered this for themselves, and then created an art that allowed the viewer to discover it too. In an abstract space, relationships come to the fore and spontaneously multiply.

Each new element adds value well beyond its intrinsic content, interacting with all the other elements in the picture. The result could be chaos, of course, subjecting the viewer to a dizzying calculus of forms, only a small subset of them meaningful. In reality, Picasso and Braque avoid that pitfall for the most part (though some of Picasso's late cubist paintings flirt dangerously with it) by carefully educating the viewer's eye to notice certain fairly obvious sets of relations first. This has the effect of progressively building a model of meaningful relations in the viewer's mind that can then be used to seek and recognize more subtle visual and linguistic plays while disregarding meaningless ones. The mind seems innately programmed to seek the same patterns over and over. The fit get fitter.

Cubism broke with a five-century-old tradition of figurative art by reaching out to a science that was becoming radically more abstract and geometric, and in the process overturning our commonsense view of the world. This move created a weak tie that connected art with a whole domain of thought that was far removed from it. And just as weak ties turn out to be better at getting you a new job than your immediate circle of friends, so they are better at producing creative breakthroughs. Connecting to the hotspot of early-twentieth-century physics and the focus on abstract geometric form that it triggered released an avalanche of new ideas into the art world, ideas that spontaneously multiplied and are still playing themselves out. Creative ideas frequently lead to exponential growth. What hasn't always been grasped is that, conversely, under the right circumstances the exponential growth of ideas can lead to creative breakthroughs.

- Richard Ogle